Science Daily News | 27 Jun 2023

Views (140)

Webb telescope detects crucial molecule in space for the first time

Astronomers detected a crucial carbon molecule in space for the first time during observations made with the James Webb Space Telescope.

Astronomers have detected a crucial carbon molecule in space for the first time using the James Webb Space Telescope.

The compound, called methyl cation, or CH3+, was traced back to a young star system located 1,350 light-years away from Earth in the Orion Nebula, according to NASA.

Carbon compounds are intriguing to scientists because they act as the foundation for all life as we know and understand it. Methyl cation is considered a key component that helps form more complex carbon-based molecules.

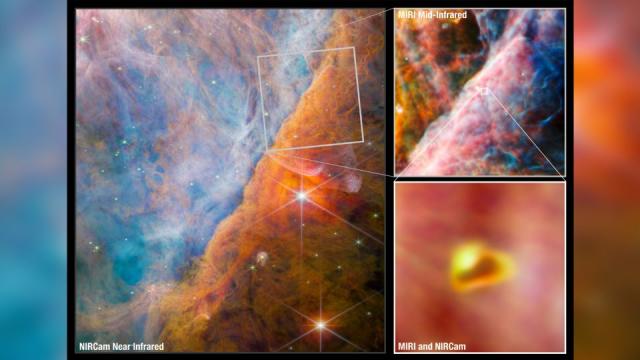

Images taken by the Webb telescope show a part of the Orion Nebula known as the Orion Bar, where UV light interacts with dense clouds of molecules. - ESA/Webb/NASA/CSA

Understanding how life began and evolved on Earth could help researchers determine if it’s possible elsewhere in the universe. The highly sensitive capabilities of the Webb telescope, which views the cosmos through infrared light that is invisible to the human eye, is revealing more about organic chemistry in space.

Red dwarf stars are much smaller and cooler than our sun, but the d203-506 system is still lashed with strong ultraviolet light from neighboring young, massive stars.

In most scenarios, UV radiation is expected to wipe out organic molecules, but the team actually predicted that the radiation could provide a necessary energy source that allows methyl cation to form.

After CH3+ forms, it leads to additional chemical reactions that allow more complex carbon molecules to build, even at low temperatures in space.

This image from Webb's Mid-Infrared Instrument shows a small region of the Orion Nebula. - ESA/Webb/NASA/CSA

While methyl cation doesn’t react efficiently with hydrogen, the most abundant molecule in the universe, it reacts well with a wide range of other molecules. Because of this chemical property, astronomers have long considered CH3+ an important building block of interstellar organic chemistry. But methyl cation wasn’t detected in space until now.

“This detection not only validates the incredible sensitivity of Webb but also confirms the postulated central importance of CH3+ in interstellar chemistry,” said study coauthor Marie-Aline Martin-Drumel, a researcher at the University of Paris-Saclay’s Institute of Molecular Sciences of Orsay in France, in a statement.

The researchers detected different molecules in the protoplanetary disk of d203-506 than those found in typical disks, and they didn’t detect any water, according to the study.

“This clearly shows that ultraviolet radiation can completely change the chemistry of a protoplanetary disk. It might actually play a critical role in the early chemical stages of the origins of life,” said lead study author Olivier Berné, research scientist in astrophysics at the French National Centre for Scientific Research in Toulouse, in a statement.

Avian flu tests after bird deaths at Forvie nature reserve

NatureScot said dead sandwich terns and black-headed gulls were found at Forvie in Aberdeenshire.

Bird flu testing has been carried out at an Aberdeenshire nature reserve after the discovery of dozens of dead birds.

Environment agency NatureScot said more than 200 dead sandwich terns and a number of dead black-headed gulls were found at Forvie National Nature Reserve.

The agency said samples had been removed for testing and the results would confirm whether it is avian flu.

The virus risk to human health is low.

Following an avian flu outbreak last year, NatureScot said that some seabird species had returned to Scotland in significantly lower numbers.

Great skuas in Shetland appeared to have been hit especially hard.

The agency said: "We are concerned about the unprecedented outbreak of avian flu over the last two years and continue to work with partners through the Scottish Task Force to ensure that we have the correct monitoring and best advice for land managers in place.

"Members of the public should avoid touching sick or dead wild birds and we would encourage visitors to coastal areas to keep their dogs on a lead to avoid them picking up dead birds."

Space tourism companies might learn a lesson from the Titan sub disaster. But are they ready to listen?

The tragedy of the Titan submersible might usher in a sea change in the tolerance of unclear hazard mitigation practices in space tourism companies.

For many experts involved in discussions over the need for (or lack of ) safety standards for the fledgling space tourism industry, the tragedy of the Titan submersible felt like their own nightmare scenario come true. But will the disaster that killed five people, including a 19-year-old university student, move the needle toward a more safety-first approach, or will arguments that innovation could suffer prevail?

Now an executive director of the International Association of the Advancement of Space Safety (IAASS), Sgobba has been waging a quiet war for years against the exemption from safety oversight guaranteed to companies developing space tourism technologies by the U.S. Congress nearly two decades ago. When reports of the catastrophic implosion of an uncertified tourist submersible during a sight-seeing trip to the Titanic wreck emerged, Sgobba couldn't fail to notice similarities.

"It is exactly the kind of scenario that would trigger a big discussion if it were to happen in a space tourism flight," Sgobba told Space.com in an interview. "In fact, we have a sort of an analogue here. You have a technology that goes into an extreme environment for the purpose of pleasure that doesn't give much chance to people to survive if something goes badly wrong."

All these claims echoed arguments that Sgobba has heard over the years from the space tourism community. But for the veteran space safety engineer, those arguments always ring hollow.

"Standards in aviation and space have evolved from prescriptive requirements, which were telling you exactly how to build a system to something that expects you to demonstrate that you have performed your hazard analysis and addressed the main safety problems," Sgobba said. "In fact, if you want to fly a coffee machine to the International Space Station, you will have to comply with the same set of standards as if you were building a whole new module. So it is a lie to say that standards mean that someone will tell you exactly how to build your system."

The Commercial Spaceflight Federation, which represents space tourism companies in the U.S., has not responded to Space.com's request to comment on the possible implications of the OceanGate saga on their own interests. In a previous interview, however, the federation's president Karina Drees, argued against such regulations, citing the stifling of innovation as a key concern — the same argument made by Stockton Rush.

"The vehicles that have been designed today are quite different from each other," Drees told Space.com at the time. "And so if regulations had been written on any one style, then that would have really prevented some of these designs from coming to the market."

It is this type of reasoning that Sgobba objects to.

"The certification is essentially a peer-review of your design by an expert," Sgobba said. "Instead of waiting for an accident, you perform your hazard analysis in advance. The solution to your hazard analysis is entirely in your design and you get input from other people who understand this matter and that can help you to make your product as safe as possible."

"There were requirements regarding safety that they had to fulfill in order to get paid for the future service," said Sgobba. "So we have over there a very clear scheme of how things should be working. The only difference is that in the future, it could not be NASA who does the certification."

For years, Sgobba has been advocating for an establishment of an independent Space Safety Institute, a non-government organization of industry experts modeled on the classification societies that oversee standards in the shipping industry and which would have been responsible for certifying the Titan submersible had it not avoided the process through a loophole.

Just like OceanGate, space tourism companies rely on informed consent, by which the participants accept risks, including the fact that they are taking a potentially life-threatening ride on an uncertified vehicle that no independent expert had seen.

In Space.com's earlier interview with the Commercial Spaceflight Federation, Drees compared the informed consent in space tourism to that signed by a patient undergoing an elective surgery, a comment that might raise eyebrows considering the heavily regulated nature of the medical sector.

The space safety community will likely closely follow how the Titan tragedy plays out in court and whether those informed consents will hold up against the years of Rush's documented disregard of other experts' opinions. Sgobba, for one, doubts they will.

"The best way to defend yourself in the case of an accident is to show that you have done things according to the rules," said Sgobba. "The fact that there was an implosion means that something was not safe and because they cannot show that they have applied the rules, there is no defense."

Christopher Johnson, a space law advisor at the Secure World Foundation, also thinks that the informed consents the Titan passengers signed are likely going to come under scrutiny.

"The idea is that the commercial actor who chooses to get into this pioneering spacecraft or submarine or whatever, chooses the level of risk they are comfortable with," Johnson told Space.com. "But to do this, the government places an obligation that an actor can only consent to the risk if they are informed of that risk. So what we can learn from this tragedy is how well and to what extent the company knew the risk and could somehow quantify or qualify that risk and convey it to their customer so that they could understand how safe that vehicle was."

Related stories:

The five people killed during the Titan implosion include OceanGate CEO Rush, British businessman Hamish Harding (who flew to space in 2022 on Blue Origin's New Shepard), French deep sea explorer Paul Henry Nargeolet, British/Pakistani businessman Shahzada Dawood and his 19-year old son Suleman.

On Monday (June 26), the company announced its June 29 target to launch its first commercial flight, called Galactic 01, which will carry three members of the Italian Air Force alongside a Virgin Galactic astronaut trainer and two pilots.

Children with illnesses given special night at zoo

About 300 people enjoy a Dream Night at the Cornwall zoo to "make precious memories", staff say.

Children with life-threatening conditions have enjoyed a special night at a zoo in Cornwall.

The Dream Night at the Zoo event in Newquay saw 300 people attend, including children's families, to give everyone an "opportunity to make precious memories", staff said.

They were invited from Little Harbour Children’s Hospice in St Austell, support charity Ellie’s Haven in Looe and the Royal Cornwall Hospital's Oncology Unit.

They had access to the zoo "for the evening and the chance to learn all about its animals from the zoo keepers and rangers", as well as other entertainment, staff said.

Newquay Zoo has been hosting events for chronically ill and disabled children, including the one last Friday, for the last five years.

Dream Night at the Zoo is a global initiative that started in the Netherlands.

On this occasion in Cornwall, staff invited children from Little Harbour Children’s Hospice in St Austell, Ellie’s Haven in Looe and Treliske’s Oncology Unit.

Mike Downman, zoo team leader of animals, said the attraction was "proud" to host it.

He said: "It means a lot to us to help create special memories that children and their families will be able to cherish.”

Ellie’s Haven general manager Sophie Libby said: "It really was a magical night and seeing how happy the children were, made it even more special."

What is a heat dome? Scorching temperatures in Texas are expected to spread to the north and east

Scorching temperatures brought on by a “heat dome” have taxed the Texas power grid and threaten to bring record highs to the state before they are expected to expand to other parts of the U.S. during the coming week, putting even more people at risk. “Going forward, that heat is going to expand ... north to Kansas City and the entire state of Oklahoma, into the Mississippi Valley ... to the far western Florida Panhandle and parts of western Alabama," while remaining over Texas, said Bob Oravec, lead forecaster with the National Weather Service. Record high temperatures around 110 degrees Fahrenheit (43 degrees Celsius) are forecast in parts of western Texas on Monday, and relief is not expected before the Fourth of July holiday, Oravec said.

“Going forward, that heat is going to expand ... north to Kansas City and the entire state of Oklahoma, into the Mississippi Valley ... to the far western Florida Panhandle and parts of western Alabama," while remaining over Texas, said Bob Oravec, lead forecaster with the National Weather Service.

Record high temperatures around 110 degrees Fahrenheit (43 degrees Celsius) are forecast in parts of western Texas on Monday, and relief is not expected before the Fourth of July holiday, Oravec said.

Cori Iadonisi, of Dallas, summed up the weather simply: “It’s just too hot here.”

Iadonisi, 40, said she often urges local friends to visit her native Washington state to beat the heat in the summer.

“You can’t go outside," Iadonisi said of the hot months in Texas. "You can’t go for a walk.”

WHAT IS A HEAT DOME?

A heat dome occurs when stationary high pressure with warm air combines with warmer than usual air in the Gulf of Mexico and heat from the sun that is nearly directly overhead, Texas State Climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon said.

“By the time we get into the middle of summer, it’s hard to get the hot air aloft,” said Nielsen-Gammon, a professor at Texas A&M’s College of Atmospheric Sciences. “If it’s going to happen, this is the time of year it will.”

“One thing that is a little unusual about this heat wave is we had a fairly wet April and May, and usually that extra moisture serves as an air conditioner,” Nielsen-Gammon said. ”But the air aloft is so hot that it wasn’t able to prevent the heat wave from occurring and, in fact, added a bit to the humidity.”

The National Integrated Heat Health Information System reports more than 46 million people from west Texas and southeastern New Mexico to the western Florida Panhandle are currently under heat alerts. The NIHHIS is a joint project of the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Multnomah County, home to Portland and known for typically mild weather, alleges the combined carbon pollution the companies emitted was a substantial in causing and exacerbating record-breaking temperatures in the Pacific Northwest that killed 69 people in that county.

An attorney for Chevron Corp., Theodore J. Boutrous Jr., said in a statement that the lawsuit makes “novel, baseless claims.”

WHAT ARE THE HEALTH THREATS?

Extreme heat can be particularly dangerous to vulnerable populations such as children, the elderly, and outdoor workers need extra support,

Symptoms of heat illness can include heavy sweating, nausea, dizziness and fainting. Some strategies to stay cool include drinking chilled fluids, applying a cloth soaked with cold water onto your skin, and spending time in air-conditioned environments.

Cecilia Sorensen, a physician and associate professor of Environmental Health Sciences at Columbia University Medical Center, said heat-related conditions are becoming a growing public health concern because of the warming climate.

“There’s huge issues going on in Texas right now around energy insecurity and the compounding climate crises we’re seeing,” Sorensen said. “This is also one of those examples where, if you are wealthy enough to be able to afford an air conditioner, you’re going to be safer, which is a huge climate health equity issue.”

____

Miller reported from Oklahoma City. O'Malley reported from Philadelphia.

____

New Zealand seeks to exterminate predators to save native birds

New Zealand plans to wipe out every last rat, possum and stoat. Can the plan work?

On a bright Sunday morning the wildlife-lovers gather in Miramar, a scenic peninsula. They are on an exterminating mission.

After donning hi-vis jackets, the volunteers are handed peanut butter - ideal bait for rodents - and poison.

Each is assigned a patch where they will check coil traps and toxin-laced bait boxes. "Good luck fellows," says Dan Coup, who leads the group.

A GPS app guides Coup through the bush to devices on his route. For each one he replaces the bait and updates the information on the app. None shows signs of a visit by a rat.

But as he surveys the ground for droppings and other clues, his phone vibrates. One participant has posted an image to their WhatsApp group: a dead rat in a trap.

This is not welcome news. "Dave will feel good that he's caught it, but we feel sad that there's still a rat," Coup sighs.

Eradicating rats and other predators is the goal not just for Miramar but for all New Zealand. The government expects the task to be completed by 2050.

Others point to practical and ethical problems.

At the heart of the project is a unique ecology. New Zealand split from an ancient supercontinent 85m years ago, long before the ascent of mammals. Without land predators, birds could nest on the ground or do without flying.

Furthermore, New Zealand was the last major landmass settled by humans. In the 13th Century Polynesians brought mice and Pacific rats. Six centuries later, Europeans introduced larger mammals that feasted on defenceless birds. Almost a third of native species have been wiped out since human settlement.

Efforts to save the others are not new. In the 1960s, conservationists managed to clear rats from small offshore islands. But tackling predators did not become a social phenomenon until about 2010.

"It bubbled up and became a national totem," says James Russell, an Auckland University biologist and champion of the 2050 project.

One factor, Russell says, was the advent of infrared cameras. In the 20th Century the most visible pests, and the targets of major culls, were large herbivores such as deer and goats. But from the 2000s, wildlife enthusiasts were able to show what small mammals were up to at night.

Politicians then got on board. In 2016 a law marked the worst predators for eradication: the three types of rats (Pacific rat, ship rat, Norway rat), mustelids (stoats, weasels, ferrets) and possums. Mid-century was chosen as an inspirational deadline.

The most ambitious of them is Predator Free Wellington. In a city of 200,000 people, it aims to kill off a range of pests, notably rats which thrive in urban environments.

The project's 36-strong team has turned amateur rat-catchers into proper exterminators. It has supplied them with anticoagulant poison, which is much more effective than traps, as well as the GPS app which stores information from every device in real time.

Cameras have been installed in hotspots. "If any rat shows up," says Predator Free Wellington director James Willcox, "my planning team know where they want to put their resources."

Every rat found dead is sent to the lab for an autopsy. This is crucial because anticoagulants, by design, kill slowly. Rats are intelligent social animals and learn to avoid things that obviously harm them.

As a poisoned rat dies away from the bait box, Predator Free Wellington needs the autopsies to monitor effectiveness.

"We cut them up to see if they've been killed by toxins," Willcox explains. "We also need to understand: is it male, is it female, has it reproduced recently? Are we chasing one rat or a family of rats?"

Miramar has been at the forefront of the city's offensive against predators. Rats are now a rarity on the peninsula and many native birds have made a comeback. The distinctive call of the tui, whose numbers in Wellington had dwindled to just a few pairs in 1990, is ubiquitous.

"In our back garden we now have tui flying over the whole time," says long-time Miramar resident Paul Hay. "The birdlife has absolutely taken off, especially in the last five years."

The city-wide effort benefits from an earlier conservation concept pioneered in Wellington: predator-proof fencing.

Behind such rigorous biosecurity measures, birds that were once rare have not just survived but are spreading out to surrounding neighbourhoods.

A year after a predator-exclusion fence was erected in 2016, the area was cleared of pests. The challenge now is make sure none get in.

Constant vigilance is of the essence. A rat might be accidentally dropped in by a bird of prey; a tree could fall on the fence, allowing a weasel to creep in.

Any damage to the fence will set off its warning system. "If the alarm goes off in the middle of the night one of us will get up there and have a look," says Nick Robson, Brook's operations manager.

Cameras and ink pads alert staff to any incursion. But the ultimate detection tool, and the predator's worst enemy, is man's best friend. "Dogs are specially trained to detect certain pests and ignore others," says Robson. "It can be that a dog can detect a rat whereas our devices haven't."

Preventing reinvasion is a concern particularly for offshore islands. Rakiura, or Stewart Island, is the largest of these. Separated from the mainland by 25km of water, it has rats but has always been mustelid-free. This relative isolation has allowed rare birds to nest there and conservationists are working hard to preserve it.

"We're holding the line," says Shona Sangster, Sircet's chairperson, as she inspects traps in the bush.

Strong defences are vital for small nearby islands that are already predator free. Rats can swim for half a mile (800m): keeping them away from those sanctuaries and the endangered birds they shelter is a constant struggle.

Government money has helped. Predator Free Rakiura, a project set up under the 2050 scheme, has provided expertise, paid staff and nifty tools such as self-reloading traps. These crush the skull of any approaching rat and require minimal maintenance: victims drop to the ground and nature does the tidying up.

Last year the group distributed traps to schoolchildren and gave out prizes for the most rats caught, the biggest rat, the one with the biggest teeth and the furriest coat.

Youngsters are raised in a community where predator control matters hugely, Sangster says. "What is slightly unusual from an outside perspective is part of their day-to-day life."

Sircet also promotes responsible pet ownership on the island. Cats - bird killers that are safe from eradication because of their appeal to humans - have to be neutered and microchipped.

Dogs, which tend to mistake kiwi for fluffy toys, can be dangerous too. Under a Sircet training programme that is voluntary (for owners, that is) an electronic kiwi delivers a mild shock to pooches that get too friendly, teaching them to give the birds a wide berth.

Holding the line is an achievement. But what are the chances of Rakiura, an area the size of Greater London, becoming completely predator-free within 27 years? Sangster is cautious on this question. "Shoot for the stars: you might land on the Moon," she says.

The feasibility of the whole 2050 project has been a matter of debate among conservationists. James Lynch, the founder of Zealandia, has reservations on grounds of practicality and cost-effectiveness.

He supports the ultimate aim of removing predators. "The problem," Lynch says, "is that we have no toolbox for this at the moment."

Most native birds, he notes, do not need a zero-predator environment to thrive. The few that do, he argues, can survive on offshore or urban sanctuaries. Rather than try to clear the whole country of pests, Lynch recommends focusing resources on woodland around fenced areas to maximise the survival of birds coming out.

That concept, he says, has worked in Wellington and represents the best hope nationwide while tools for complete eradication are being developed.

Others regard the very idea of a predator-free New Zealand as fanciful. Conservation researcher Wayne Linklater points out that over the past 150 years, New Zealand has lost every war it has waged on rabbits, deer and other pests.

Campaigns to exterminate intelligent, sentient beings are not just unworkable but ethically misguided, Linklater adds. "We marshalled enormous resources and people's passion and we implemented great cruelty. How could we be so blithe with suffering?"

The drive to purge society of nefarious forces, the mass mobilisation and slogans remind Linklater of evangelical zeal. The predator-free movement, he says, "depends on demonising a species and making an enemy of that species so that you can kill it".

Besides, who is Homo sapiens, that most invasive of mammalian predators and systematic destroyer of habitat, to declare total war on creatures it brought with it?

Instead of setting impossible national targets, Linklater recommends allowing communities to determine their own biodiversity goals. Auckland residents could live with a few rats and possums, while Stewart Islanders might prioritise protecting their kiwis and muttonbirds.

For biologist James Russell, who did much to give scientific backing to the 2050 project, localised strategies are pointless. "It's the unambitious, business-as-usual model," he shrugs.

Saving birds in a few places, he goes on, is a false economy: it requires perpetual investment to stop predators returning. Eradication is expensive but "you pay it once, and then it's done."

Russell concedes that no-one knows how to finish the job yet. Pest-control technology, however, has made huge strides since the 1960s: who knows what continued investment can achieve over the next 27 years?

As for moral objections, there are no hard and fast answers. It is up to individuals and societies to weigh complex arguments. New Zealanders, Russell says, have collectively decided that sacrificing some species to save others is the right thing to do.

It is true that, right now, opposition to eradication is subdued and enthusiasm prominent.

Back on the Miramar peninsula, Dan Coup looks forward to the day when he and his fellow rat-catchers are finally redundant.

"You've got a choice to either keep working for ever, or you invest a huge amount up front to get the last half-a-percent of the rats and then you don't have to work again," he says.

0 Likes