Science Daily News | 20 Jul 2023

Views (105)

Rocket Lab recovers Electron booster from Pacific Ocean after satellite launch (photos)

Rocket Lab pulled one of its boosters from the sea after a launch on Monday (July 17), taking another step toward rocket reuse.

Rocket Lab pulled one of its boosters from the sea after a launch on Monday (July 17), taking another step toward rocket reuse.

A Rocket Lab recovery ship motored out to the splashdown zone in short order, and crewmembers successfully pulled the booster from the sea.

RELATED STORIES:

Those larger launchers come back to Earth for powered vertical touchdowns, but the Electron is too small to have enough fuel left over for such maneuvers after launch. So Electron boosters must make a more passive return to their home planet.

New studies shed light on how genes might shape a person’s experience with Covid-19

There are myriad factors that may determine how people fare after they catch Covid-19, including their viral dose and underlying health. New research is exploring another dimension to the puzzle of how people experience this infection: genes.

About 20% of people who caught Covid-19 only knew they had it because it showed up on a routine screening test. They never had any symptoms. Others got it and couldn’t shake its aftereffects for months, going on to be diagnosed with long Covid.

There are myriad factors that may determine how people fare after they catch Covid-19, including their viral dose; where the virus first entered the body — the nose or maybe mouth or eyes; their age and underlying health; and the genetic characteristics of the variant that infected them, to name a few.

New research is exploring another dimension to the puzzle of how people experience this infection: genes.

Another study, which was recently posted online as a preprint ahead of peer review and publication, found that individuals with certain changes to genes near FOXP4, which codes for a protein active in the lungs and immune system, appear to be more likely to develop long Covid.

HLAs may ring a bell because they’re used to determine whether organs are compatible with patients who need transplants. These molecules stick up from the surface of certain white blood cells, as well as cells in many other tissues of the body.

“I kind of think of them as like an arm sticking up, and a hand at the end of the arm,” said study author Dr. Jill Hollenbach, a professor of neurology the University of California at San Francisco’s Weill Institute for Neurosciences.

Hollenbach says it’s the job of HLA molecules to present pieces of proteins to the immune system so they can be recognized if they’re ever encountered again.

Imagine, she says, in a cell that’s ingested the virus that causes Covid-19, some of that virus gets broken down in the cell, and some of its protein fragments would migrate up to the surface, where HLA molecules would grab them and hold them out so T cells could see them.

T cells are immune cells that help the body recognize and remember proteins. They build a memory for the immune system so it can respond if it sees a pathogen again.

So the HLA molecule is sticking up like an arm “then held in the hand is this … small peptide fragment piece of a protein from the virus,” Hollenbach said.

There are three general groups of HLA: HLA-A, HLA-B and HLA-DR. Within these groups, there are hundreds of variations of these molecules. Hollenbach says each one will very specifically look for certain kinds of protein fragments and hold them in a certain way so T-cells can see them and learn to make antibodies against them.

For the study, Hollenbach started with people who had been HLA-typed for a large registry of potential bone marrow donors called “Be The Match.” She invited more than 29,000 to enroll in a smartphone-based study where people reported positive test results and recorded their symptoms. The initial “discovery” group consisted of more than 1,400 people who were unvaccinated and reported they’d tested positive for Covid-19; 136 of them reported no symptoms associated with their infections.

The researchers then took a closer look at this group to see if there were any similarities in the genes that coded for their HLA molecules, and there were. People in this group were more likely to carry a gene that coded for a specific kind of HLA molecule called HLA-B*15:01.

People who had two copies of genes were eight times more likely to remain asymptomatic than those who didn’t carry these variants.

Next, Hollenbach wanted to know how that particular kind of HLA molecule might be preventing a person from getting symptoms.

It turns out that HLA-B*15:01 recognizes pieces of other kind of SARS viruses that are associated with common, seasonal respiratory infections. The protein fragments it recognizes are shared with the virus that causes Covid-19. So folks with these HLA molecules likely already had some preexisting immunity against SARS-CoV2 and were able to clear the virus before it caused symptoms, Hollenbach said.

About 20% of people who get Covid-19 won’t have any symptoms. This HLA variant is carried by about 20% of them, Hollenbach said. So it’s not the only explanation for while people might have silent infections, and researchers point out that carrying HLA-B*15:01 doesn’t guarantee that a person won’t have any symptoms.

“Doubtless there are other genetic and non-genetic factors that are important, but we don’t know what those are right now,” Hollenbach said. “We do know that in this case, this particular genetic factor is strongly associated with asymptomatic infection.”

Genes may also help explain why people end up on the other side of the Covid-19 spectrum, dealing with symptoms that linger and turn into long Covid.

For more than three years, an international group of scientists have been searching for genes that may be associated with severe Covid-19 infections.

The investigation into long Covid is an offshoot from that effort, led by scientists at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm.

An analysis of 11 of those studies, which involved sequencing all the genes in a person’s body, and then comparing the genomes of large numbers of people, found that those who developed long Covid were likely to share DNA around a gene called FOXP4, a gene which seems to be involved in immune responses in cells in the tiny air sacs of the lungs. These cells also seem to help repair damage to the lung.

“This particular genetic variant is intriguing because it offers some insights into some underlying mechanisms associated with long Covid and suggests the presence of a genetic predisposition. However, it cannot be solely relied upon to identify individuals at risk,” said lead study author Dr. Hugo Zeberg, who is an evolutionary geneticist at Karolinska.

Genes, Zeberg said, are likely only one part of reason why someone develops long Covid, and there are probably a slew of genes involved.

“As far as I know, it has never been shown that long COVID has a genetic component. So that’s a very important discovery,” said Dr. Noam Beckmann, who is the director of data driven science at the Mount Sinai’s Icahn School of Medicine in New York City.

Beckmann is part of a team of scientists from 16 different countries who contributed data to the study.

People who carried this version of the genes around FOXP4 had about a 60% greater odds of developing long Covid compared with people who didn’t have the variant, according to the study, which was posted as a preprint ahead of peer review.

Zeberg said their group plans to collect more cases and add them to the investigation, which he hopes will point to other genes that may be involved, too.

“We hope that our results, will spur others in the scientific community to investigate these associations further,” he said.

Diagnostic errors linked to nearly 800,000 deaths or cases of permanent disability in US each year, study estimates

Misdiagnosis of disease or other medical conditions leads to hundreds of thousands of deaths and permanent disabilities each year in the United States, according to a report published this week.

About 371,000 people die and 424,000 sustain permanent disabilities – such as brain damage, blindness, loss of limbs or organs or metastasized cancer – each year as a result.

To make the estimate, researchers pulled from dozens of earlier studies to assess how often certain conditions were missed and how often that miss led to serious harms. That risk was then scaled by the incidence rate of new cases in the total US population.

“Patients should not panic or lose faith in the health care system,” the researchers wrote in the study. Overall, there’s less than a 0.1% chance of serious harms related to misdiagnosis after a health care visit.

Nearly 40% of those severe outcomes including death and permanent disability are linked to errors in diagnosing a group of five conditions: stroke, sepsis, pneumonia, venous thromboembolism (a blood clot in a vein) and lung cancer.

“These are relatively common diseases that are missed relatively commonly and are associated with significant amounts of harm,” said Dr. David Newman-Toker, a neurologist at Johns Hopkins University. He led the study’s research team from the Johns Hopkins Armstrong Institute Center for Diagnostic Excellence, in partnership with researchers from the Risk Management Foundation of Harvard Medical Institutions Inc.

Although those five conditions aren’t the most frequently misdiagnosed, they have the largest impact, and the study findings can help prioritize areas for investment and interventions, he said.

Spinal abscess, an infection of the central nervous system, is misdiagnosed more than 60% of the time, according to the report. But with 14,000 new cases each year overall, that leads to about 5,000 serious harms – a relatively small portion of the overall burden of diagnostic error.

But stroke, which the report found to be the top cause of serious harms, is a relatively common condition with a high risk of severe outcomes, and it’s misdiagnosed more often than average. About 950,000 people have a stroke each year in the US, and it’s missed in about 18% of cases, according to the report – leading to about 94,000 serious harms each year.

Diagnostic errors are typically the result of attributing non-specific symptoms to something more common and perhaps less serious than the condition that is actually causing it, experts say.

“Occasionally, we have people who get inappropriate treatments for a disease they don’t have, and they suffer harms from that,” Newman-Toker said. “Much more common is a life-threatening disease that is missed because the manifestations are milder or less obvious.”

When someone has trouble speaking and moving an arm, it’s easy to diagnose a stroke. But a stroke can also cause dizziness or headache, which can be symptoms of many other things.

Heart attacks can also cause vague symptoms such as general chest pain. But they are significantly less likely to be misdiagnosed, with less than a 2% error rate, according to the report.

The success in diagnosing heart attacks required decade of concentrated efforts, Newman-Toker said. The process started by recognizing that misdiagnosis was a problem, which led to investment of funds into research and regulatory requirements around monitoring performance.

“You end up ultimately with a system of care that focuses on not missing heart attacks,” he said. “It’s the model for what we could be doing.”

Generally, though, diagnostic errors are different than other areas of patient safety – such as surgeries that are done on the wrong site, falls or medication errors – because the link between an action and a result is less direct, said Dr. Daniel Yang, an internist and program director for the diagnostic excellence initiative at the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

“Diagnostic errors are errors of omission,” said Yang, who was not involved in the new study. “The question is: Could [the outcome] be prevented if we had done something differently earlier on? Oftentimes, that’s a judgment call that two doctors might disagree on.”

And broader systemic issues in the health care system challenge that process.

“The diagnostic journey is really not a single decision at one point of time,” Yang said. “It’s an odyssey that unravels overnight, in some cases, days, weeks, months, even years. It cuts across multiple care settings and different types of doctors.”

But various points of care are disconnected, and providers often don’t have a full understanding of patient’s history, he said. That fragmentation – with scattered records from each encounter with primary care, specialists, clinics and emergency rooms – presents opportunities for information to be lost along the way, leaving the patient to put all the puzzle pieces together on their own.

The study specifically captures diagnostic error among patients seen in health care settings. But the burden is probably significantly larger when factoring in all those people who didn’t seek care and can’t receive optimal treatment because their diagnosis is happening later than it should, Yang said.

“The hospital can provide perfect diagnostic care. But if someone spends months waiting to see a doctor in the first place, it doesn’t matter how good the health care system is, because the stage of diagnosis is going to be later,” he said.

You can see Mars, Venus and Mercury near the crescent moon tonight. Here's where to look.

Mars, Venus and Mercury will appear close to a thin crescent moon tonight (July 19), but you'll need to get out right at sunset to make the most of this grouping of inner solar system bodies.

Hopefully the skies in your area are clear tonight (July 19), because there will be an excellent grouping of celestial bodies shortly after sunset.

From New York City, the quartet should appear to the west just as the skies begin to darken at sunset. Note that the three planets and the moon will already be fairly low in the sky by the time it gets dark, so you'll need to have a decent view of the horizon to make the most of this skywatching opportunity.

TOP TELESCOPE PICK:

Go in the opposite direction from Venus — above and to the left — to see the steady glow of red-orange Mars.

The four bodies will be in the Leo constellation, making this a good opportunity to familiarize yourself with the stars of this popular night sky sight. The moon will be underneath the Lion's jaw, while Venus will be located between its front legs. Mars will be just beside one of its rear feet.

On Thursday (July 20), Mars will move even closer to the moon. Head outside around the same time on the following two nights and look to the west to watch the cosmic dance of these summer skywatching favorites.

Editor's Note: If you snap an image of the moon beside Mars, Venus and Mercury and would like to share it with Space.com's readers, send your photo(s), comments, and your name and location to spacephotos@space.com.

Bereaved mother opens New Forest residential retreat

Corinne Bespolka decided to restore a derelict cottage after her teenage son died suddenly in 2003.

When Cameron Bespolka died in an avalanche in the Austrian Alps ten years ago he was just 16-years-old. To help deal with the grief his family decided to carry on his passion for wildlife. After several years of fundraising they have finally opened a residential retreat in the New Forest to help young people connect with nature.

She and her family - who are from Winchester, in Hampshire - set up the Cameron Bespolka Trust and started fundraising just after Cameron's death.

Their aim was to raise money to restore a derelict cottage inside a 1,000-acre RSPB nature reserve near Normansland.

"One of our ways of really dealing with a lot of grief that we went through - losing a child is the worst thing that can happen to you - is carrying on Cameron's passion," Mrs Bespolka said.

The teenager loved animals and being outside.

"When he got to 11 he realised that whenever he was outside, wherever he was, there were always birds, and it was that that attracted him," Mrs Bespolka explained.

After four years of work to restore the building, Cameron's Cottage opened in May.

It provides a residential retreat for 15 to 25 years old, offering them opportunities to learn more about wildlife and conservation skills.

"We felt it was a living legacy for Cameron," Mrs Bespolka said.

"I think he would be proud. I think one of the things he would have really loved is how much he has left us with."

Young carers, the University of Winchester and Totton College are some of the groups who use the cottage regularly.

Mrs Bespolka said the project had gone "way beyond" what the family ever imagined.

"Cameron would have loved that and would probably have been volunteering," she added.

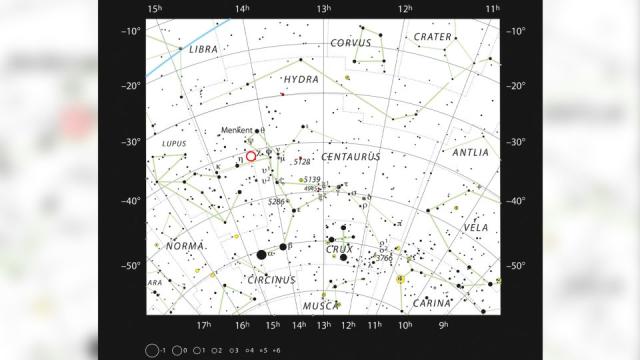

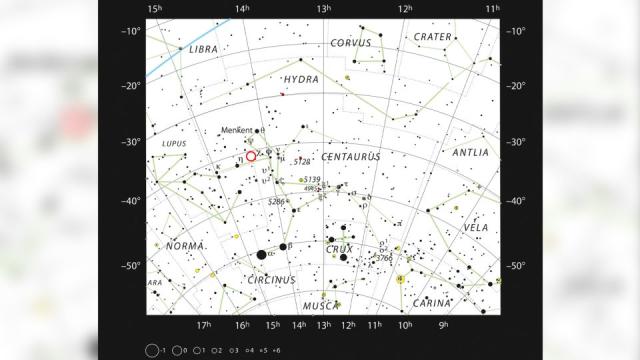

Rare ‘Trojan’ world may share the same orbit as another planet

Astronomers spotted a possible “sibling” planet that shares the orbit of another exoplanet in a system located 370 light-years away.

Astronomers may have found a rare “sibling” that shares the same orbit of a Jupiter-like planet around a young star.

The scientists believe their direct image may be the strongest evidence to date showing that two exoplanets can share the exact same orbit.

A study detailing the findings was published Wednesday in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

“Two decades ago it was predicted in theory that pairs of planets of similar mass may share the same orbit around their star, the so-called Trojan or co-orbital planets. For the first time, we have found evidence in favour of that idea,” said lead study author Olga Balsalobre-Ruza, a postdoctoral student of astrophysics at Madrid’s Centre for Astrobiology, in a statement.

Evidence for Trojans beyond our solar system — specifically Trojan planets — has been sparse until now.

“Exotrojans (Trojan planets outside the Solar System) have so far been like unicorns: they are allowed to exist by theory but no one has ever detected them,” said study coauthor Jorge Lillo-Box, a researcher at the Centre for Astrobiology, in a statement.

Trojans can typically be found in Lagrangian points, or the two extended regions within a planet’s orbit where both the gravitational pull of the star and planet can trap materials.

The discovery has caused researchers to question how Trojans form and evolve and just how many could exist in other planetary systems, said study coauthor Itziar De Gregorio-Monsalvo, the European Southern Observatory’s head of the Office for Science in Chile, in a statement.

During observations of the planetary system, the research team noticed a debris cloud at a point in PDS 70b’s orbit where Trojans might exist. The signal suggested a cloud of debris with a mass of about twice that of our moon, which could be a Trojan planet or a planet in formation.

“Who could imagine two worlds that share the duration of the year and the habitability conditions? Our work is the first evidence that this kind of world could exist,” Balsalobre-Ruza said. “We can imagine that a planet can share its orbit with thousands of asteroids as in the case of Jupiter, but it is mind blowing to me that planets could share the same orbit.”

In order to confirm the discovery of a true Trojan world, the researchers will have to wait until after 2026, when they can use ALMA to see just how far PDS 70b and the debris cloud have progressed in their long orbital period around the star.

“This would be a breakthrough in the exoplanetary field,” Balsalobre-Ruza said.

0 Likes