Science Daily News | 15 Jun 2023

Views (147)

Orcas were spotted swimming unusually close to Massachusetts

New England Aquarium scientists photographed four killer whales near Nantucket as they were conducting an aerial survey of the area.

New England Aquarium scientists photographed four orcas near Nantucket on Sunday.

Orcas have been behind a spate of recent boat attacks near Spain.

It's rare for killer whales to venture into North Atlantic waters.

Katherine McKenna, an assistant research scientist at the aquarium's Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life, was the one who first saw the orcas.

"Initially I could just see two splashes ahead of the plane," she said in the press release. "As we circled the area, two whales surfaced too quickly to tell what they were. On the third surfacing, we got a nice look and could see the tell-tale coloration before the large dorsal fins broke the surface."

"I think seeing killer whales is particularly special for us because it unlocks that childhood part of you that wanted to be a marine biologist," Orla O'Brien, an associate research scientist who leads the aquarium's aerial survey team, said in the press release.

Pheasant shoots: Job loss claim over tighter Wales rules

A pub owner who relies on the industry says he is worried he may have to close for part of the year.

Stricter regulation of pheasant and partridge shooting in Wales could cost jobs in rural communities, businesses have warned.

One pub owner said he was worried he may have to close for part of the year.

Under new proposals gamebirds would only be able to be released into the countryside under licence.

The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), which backs the plans, said it would help address large-scale shoot environmental concerns.

Jonathan Greatorex, owner of The Hand in Llanarmon Dyffryn Ceiriog, in Wrexham county borough, said his business relied on a thriving shooting industry locally.

"Some think of it as wealthy people turning up in Range Rovers, shooting pheasants and then disappearing back to London," he said.

"But from our point of view, shooting sees us through the winter months - it's what keeps us alive as a business and an employer.

"I have 25 people who are reliant on us for their livelihood and without shooting, those jobs are gone for a big chunk of the year."

A public consultation ends next week, with the proposals having already led to angry exchanges in the Senedd.

Climate Change Minister Julie James sparked outrage in the shooting industry by describing "killing anything as a sport or leisure" as not something "any civilised society should support".

Gamekeeper Helen Jones, of Cwm Fedw Country Sports, said it had raised fears the changes were a first step towards an outright ban - something the Welsh government has denied.

She runs shoots at her farm in Powys and turns the game meat into delicacies like pheasant tikka bites and scotch eggs.

She questioned why more rules were needed, when those releasing birds within or near sensitive sites already have to ask for consent from Natural Resources Wales (NRW).

RSPB Cymru's head of species Julian Hughes said the charity was concerned about the impact of releasing large numbers of gamebirds on habitats and the risk of spreading diseases like avian flu.

It is estimated between 0.8 and 2.3 million birds are released into the Welsh countryside each year.

"At a high density that can have a real impact... on birds we're trying to save," he said.

NRW was asked to develop proposals for regulation of gamebird releases by the Welsh government.

It follows a similar debate in England, where campaign group Wild Justice took the UK government to court.

Mannon Lewis, principal adviser at NRW, said the idea was to bring in a permitting system for releases within or 500m (1,640 ft) near to sensitive sites.

Gamekeepers would have to apply and pay for a licence, which would set conditions based on the features in those protected sites.

Those wanting to release birds elsewhere would also have to apply for a general licence - though this would be free of charge.

"We fully recognise that many of the shoots currently in existence have done a lot of extremely good work for conservation in Wales," she said.

"It's not a ban - it's a consultation on regulating especially in those areas where there are unsustainable releases of birds which do cause problems."

A spokeswoman for the Welsh government said the consultation provided "an opportunity for all with an interest to express their views."

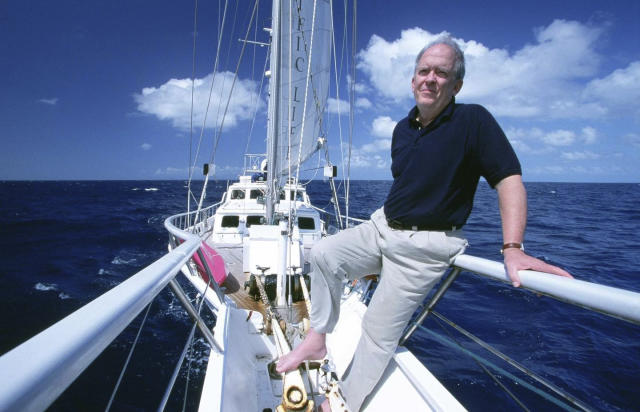

Roger Payne, who found out that whales could sing, dies at 88

Roger Payne, the scientist who spurred a worldwide environmental conservation movement with his discovery that whales could sing, has died. Payne made the discovery in 1967 during a research trip to Bermuda in which a Navy engineer provided him with a recording of curious underwater sounds documented while listening for Russian submarines. Payne identified the haunting tones as songs whales sing to one another.

Roger Payne, the scientist who spurred a worldwide environmental conservation movement with his discovery that whales could sing, has died. He was 88.

Payne made the discovery in 1967 during a research trip to Bermuda in which a Navy engineer provided him with a recording of curious underwater sounds documented while listening for Russian submarines. Payne identified the haunting tones as songs whales sing to one another.

He saw the discovery of whale song as a chance to spur interest in saving the giant animals, who were disappearing from the planet. Payne would produce the album “Songs of the Humpback Whale” in 1970. A surprise hit, the record galvanized a global movement to end the practice of commercial whale hunting and save the whales from extinction.

Payne was cognizant from the start that whale song represented a chance to get the public interested in protecting an animal previously considered little more than a resource, curiosity or nuisance. He told Nautilus Quarterly in a 2021 interview that he first heard the recording in the loud engine room of a research vessel and knew almost instantly that the sounds were indeed whales.

"In spite of the racket, what I heard blew my mind. It seemed obvious that here, finally, was a chance to get the world interested in preventing the extinction of whales,” he told the magazine.

Payne died Saturday of pelvic cancer. He lived in South Woodstock, Vermont, with his wife, the actress Lisa Harrow. Funeral arrangements have not yet been made, Harrow said.

Payne had four children from a previous marriage to zoologist Katy Payne, with whom he collaborated. The two used primitive equipment in the late 1960s to record the sounds of humpback whales, which sometimes sing their eerie, complex songs for longer than a half-hour at a stretch.

The impact of the whale song discovery on the nascent environmental movement was immense. Many anti-war protesters of the day took on saving animals and the environment as a new cause, and the words “save the whales” became ubiquitous on tote bags and bumper stickers.

Whale songs would enter the popular imagination via everything from a 1971 episode of “The Partridge Family” to a 1979 issue of National Geographic that included a flexi disc with excerpts from “Songs of the Humpback Whale.” It remains the best-selling environmental album in history.

Payne founded Ocean Alliance in 1971 to advocate for the protection of whales and dolphins. The organization operates to this day in Gloucester, Massachusetts. It has played a role in watershed moments in the history of whale protection, such as the 1972 passage of the Marine Mammal Protection Act by the U.S. Congress and the 1982 commercial whaling moratorium passed by the International Whaling Commission.

The world has lost a giant of environmental conservation with Payne's death, said Iain Kerr, the chief executive officer of Ocean Alliance and a longtime collaborator with Payne. Payne retired two years ago.

“He had a presence and a way of connecting to people that led them to dedicating their lives to protecting whales and our planet Earth,” Kerr said.

Payne was born in New York City and educated at Harvard University and Cornell University, where he received his doctorate. Early in his career as a biologist, he studied bats and birds.

He met Harrow, his widow, in 1991 at a rally for whale protection at Trafalgar Square in London. They married within 10 weeks of meeting.

“The way his mind worked was a constant joy,” Harrow said. “He was constantly seeking answers, to seemingly constant questions.”

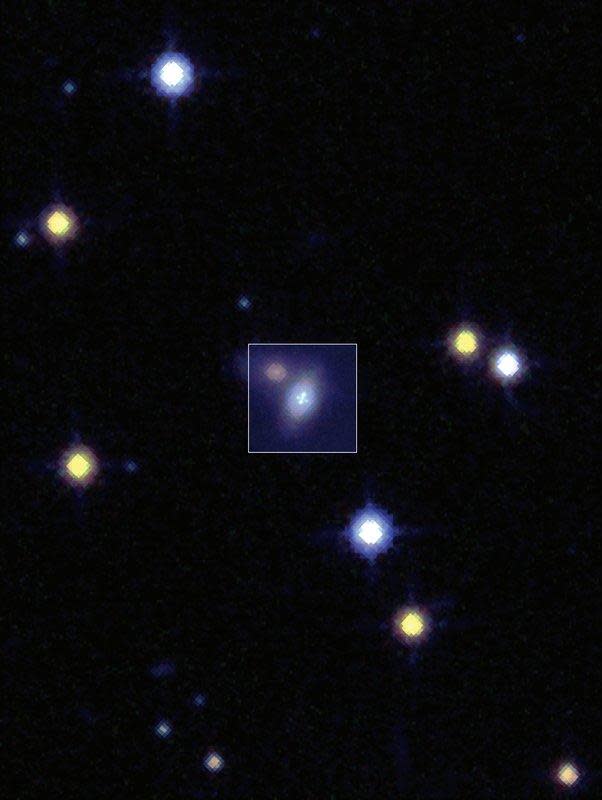

Astronomers capture "bizarre" star explosion warped by gravity

The "very rare" star explosion was so warped that it looked like multiple images in the sky.

Seeing a supernova, or an exploding star, is a unique spectacle in itself. But recently, astronomers have found something even more unique: A star explosion so "extremely warped" that it looked like it was multiple images in the sky.

So how did this happen?

"I was observing that night and was absolutely stunned when I saw the lensed image of SN Zwicky," they said. "We catch and classify thousands of transients with the Bright Transient Survey, and that gives us a unique ability to find very rare phenomena such as SN Zwicky."

SN Zwicky is a Type Ia supernova, which according to Caltech, involves a star going out with a bang.

"These are dying stars that end their lives with a light show that is always the same in brightness from event to event," Caltech said in its news release.

Study co-author Joel Johansson said this type of supernova lets researchers "see further back in time because they are magnified."

"Observing more of them will give us an unprecedented chance to explore the nature of dark energy," Johansson said.

Rare occurrences like SN Zwicky also help scientists "probe the amount and distribution of matter at the inner core of galaxies," the study's lead author Ariel Goobar said – and could even help uncover secrets of the universe.

To fight berry-busting fruit flies, researchers focus on sterilizing the bugs

Paul Nelson is used to doing battle with an invasive fruit fly called the spotted wing drosophila, a pest that one year ruined more than half the berries on the Minnesota farm he and his team run. Nelson and other growers may someday get a new tool as a result of research at North Carolina State University into the insects, which ruin the berries by laying their eggs in them and have been estimated to cost growers hundreds of millions of dollars annually.

“It’s a pest that if you’re not willing to stick the time into it, it’s going to take over your farm,” said Nelson, the head grower at Untiedt's, a vegetable and fruit operation about an hour west of Minneapolis.

Nelson and other growers may someday get a new tool as a result of research at North Carolina State University into the insects, which ruin the berries by laying their eggs in them and have been estimated to cost growers hundreds of millions of dollars annually. The researchers, using a concept called “gene drive,” manipulated the insects' DNA so that the female offspring would be sterile, and the method they used to achieve it significantly reduced the chance that a population could rebound.

The researchers, whose work was published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found if they bred one of their modified flies with a non-modified fly, up to 99% of the offspring would inherit the sterility trait. They used mathematical modeling to show that if they released one modified fruit fly for every four that were not and did that every two weeks, they could collapse a population in about five months.

Genetically modifying insects as a form of pest control isn’t a new idea. Scientists have already released genetically modified mosquitoes, for instance, which mate with the native population to produce offspring that die before adulthood to hold down populations and help combat the spread of insect-borne diseases like yellow fever, dengue and Zika viruses. But the technology hasn’t taken off as widely in agriculture because pesticides have been cheaper and easier to deploy.

Max Scott, a professor of entomology and a co-author of the paper, said some methods of releasing genetically modified insects to curb populations would become expensive if applied on a large scale because it has to be done over and over again before pests are wiped out. But he said his team's method, which hinges on an idea called “gene drive,” more quickly facilitates the spread of sterility throughout successive generations, and that could mean fewer times the modified bugs need to be released.

“We’re really excited about this,” Scott said. “The system is working really efficiently.”

At Untiedt's, Nelson said he's noticed warmer winters and earlier springs. He's still waiting to see this year's first fruit flies, but they've been coming earlier each year to the farm's roughly 35 acres of strawberries, raspberries and tomatoes, he said.

“For years they kept telling us you’ll never see (spotted wing drosophila) in your June-bearing strawberries because they’re done too early. That’s not true. We’ve found them in our June-bearing strawberries,” he said.

To combat the pests, Nelson and his team have used pesticides and traps and spend significant time looking for the tiny bugs. Hutchison said some farmers use ventilated netting or plastic that effectively creates a type of greenhouse over their fruits. But all those methods have drawbacks. Pesticides can kill beneficial insects, and spraying can require farmers who let people pick their own berries halt operations for a few days. Netting can be tough to set up, and plastic coverings can overheat crops.

Luciano Matzkin, an associate professor of entomology at the University of Arizona, studies drosophila and other pest species with an eye toward agriculture. Matzkin, who was not part of the study, said Scott's team's focus on stopping the pest by sterilizing females solved a problem that sometimes occurs with gene drive technology — that a lucky gene mutation can arise and get passed down, resisting what scientists were hoping to achieve.

Lyric Bartholomay, a professor in the School of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who studies integrated pest management and public health entomology who was not part of the study, said “increasingly tailored genetic approaches” will be necessary in the future to protect crops and people from pests, especially as insecticide resistance increases.

The research is years away from practical application. Scott and his team are moving on to more lab trials to see if their mathematical modeling is correct, and would then go through a regulatory process before moving to field trials. More research will also be needed to take into account considerations like regional genetic variation within the same species and the ecological impact of interactions with other species, something both Scott and Matzkin highlighted.

Matzkin said if there are no negative environmental risks, “a successful bio-control approach is always preferable” to pesticides, which have significant environmental consequences and costs of their own. That's why, he says, entomology departments across the country are studying the biology and ecology of the insects at the same time that other researchers work on transgenic approaches to population control in a wide array of pests.

In the meantime, Nelson will wait to see whether new solutions arise to help him manage pests. He farms with his 24-year-old son and says he's concerned about the future.

“The experts are all going to tell us what’s going on. But as we farm, we look at it, how is this going to change things for the next generation?” he asked. “If we lose our sales on our crops of berries, that’s a very large deal for our farm."

__

__

Chemical traces offer evidence of the universe's earliest stars

An international research team has found the first chemical traces of some of the oldest stars in the universe.

HONG KONG — An international research team has found the first chemical traces of some of the oldest stars in the universe.

“Astronomers had speculated that in the early universe, there were stars that could be extremely colossal,” Zhao Gang, a researcher from the National Astronomical Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences and one of the study’s authors, told NBC News. “Scientists had been trying to find the proof for decades.”

Zhao and his team found that so-called first-generation stars, which lit up the universe as early as 100 million years after the Big Bang, could have had a mass as much as 260 times that of the sun, which matched the predictions of astronomers.

First-generation stars had short lives that ended in partial explosions and can be detected only through the chemical signatures they left in the generation of stars that succeeded them. Those first-generation stars could become parent stars to the later-generation stars that bequeath their chemical signatures.

Meanwhile, the first-generation stars were made almost entirely of hydrogen and helium, while current stars contain more metal elements. Thus, researchers were looking for stars without many metal elements.

The researchers focused on a star named LAMOST J1010+2358, which has particular chemical characteristics. After researchers matched its chemical spectrum with the theoretical models, they confirmed that the parent star of LAMOST J1010+2358, the first-generation star, had 260 times the mass of the sun.

“The first-generation star we observed has the potential to become the oldest star we have ever seen,” said Alexander Heger, a professor in the school of physics and astronomy at Monash University in Australia who was part of the research team. “It probably had only lived for 2 1/2 million years and then exploded.”

Heger added that it was important to investigate first-generation stars because “this is how it all begins.”

“It’s about understanding our origins and the origins of the universe,” he said. “So far, this is sort of a blind spot in our understanding of the entire history of the universe.”

Quentin Andrew Parker, director of the Laboratory for Space Research at the University of Hong Kong, said this kind of evidence was extremely difficult to find.

“It’s like looking for a needle in a haystack because our galaxy is made up of billions and billions of stars,” said Parker, who was not involved in the research.

The findings were based on observations from two of the largest land-based telescopes in the world, the Large Sky Area Multi-Object Fibre Spectroscopic Telescope (LAMOST) near Beijing and the Subaru Telescope in Hawaii, which is operated by the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan.

“LAMOST has proved to be extremely efficient, taking spectra for vast numbers of stars,” Parker said. “You can take 4,000 spectra of 4,000 different objects at the same time.”

Parker said the research team’s success was not only a matter of fundamental science but also a result of “wonderful international collaboration,” citing the use of two telescopes operated by two nations and the talents of different researchers.

“If you just work in your silos and a nation here and you’re not allowed to collaborate with people around the world, then you don’t get the full picture,” he said. “You don’t have the right expertise. You don’t have the right insights.”

“That’s how modern science works at its best.”

0 Likes